[unable to retrieve full-text content] Angel Nova smells like raspberries, ripened to the maximum…

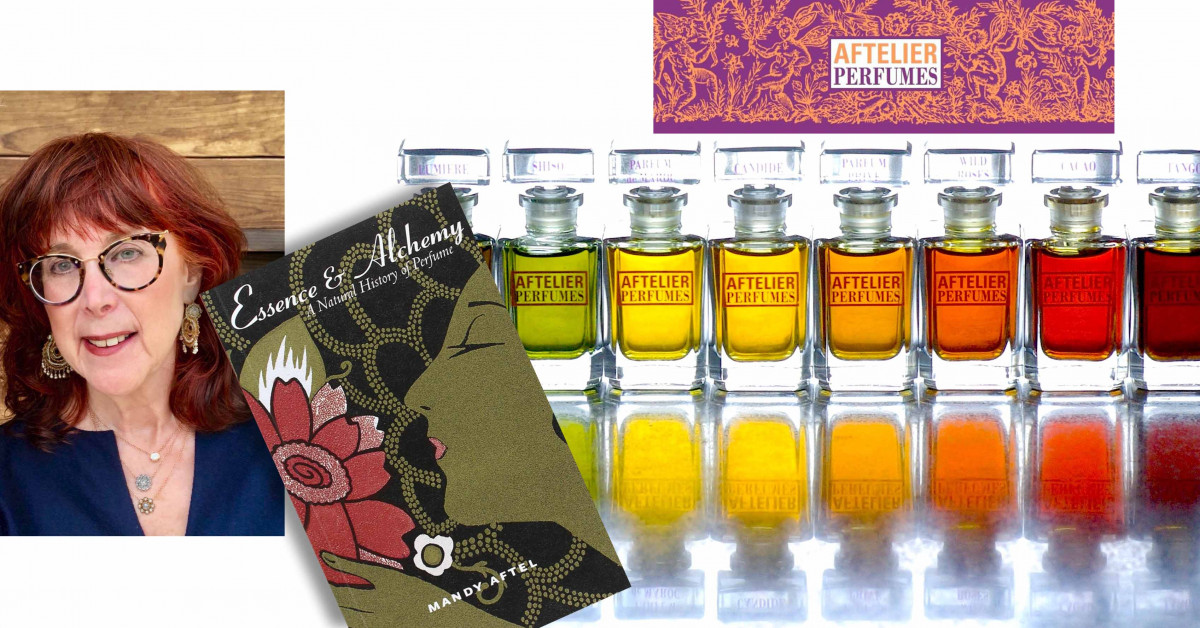

Rich and Tangled History: Perfumer and Author Mandy Aftel

Mandy Aftel is a rare mind in perfume, indulging in constant inquiry, but with a firm resolve to live in the “now.” She is one of the most accomplished writers, perfumers, and creators in American perfumery; certainly among natural perfumers. She’s authored three books about perfume, two about flavors and their integration with scent, in addition to other volumes. She teaches, built and runs a museum of smells (full of perfume history,) and has a line of perfume, Aftelier, that attracts both everyday buyers and high profile clients, many of whom eventually consult her for bespoke work. Mandy’s book “Essence and Alchemy” (2001) has been translated into numerous languages and remains a best seller to this day, opening the door to much of the secrecy that has shrouded ancient perfume knowledge, and ushering in a new awareness of what scent’s history has to say to the contemporary world.

Her ability to communicate so well has also meant that she’s often asked to write and speak on the topic of perfume, natural essences, perfume history, flavor and cuisine. It’s common to hear Mandy answering questions on NPR, or offering advice to Elle Magazine, being profiled by Huffington Post or chatting affably on podcasts. Because she has been a trailblazer, particularly in research and working with natural ingredients, many in the media reach out to her for the knowledge she can impart. But it may be her approachable, common-sense, thoughtful, purpose-driven demeanor that draws such minds to her. She has very few secrets – she shares what she knows. Some might find this disarmingly honest, but it’s such a welcomed balm of realism in a realm of creativity that is often veiled and guarded.

Yet, what do we know about Mandy’s interior world, how she works, what propels her pursuit of capturing experience through scent in the present time? I was fortunate to have a morning with Mandy to discuss any and all topics: Her perfumes, her books, collaborations, museum, her working process. She left no doors closed, and I found our questions and answers were like an engaging and happily wandering conversation that swam from idea to idea effortlessly. Mandy is also a great Fragrantica enthusiast, and embraced the opportunity to share more about her world with our readers. She mentioned that when she speaks to people in her museum (The After Archive of Curious Scents,) she’ll often refer them to Fragrantica to help answer their questions about “What sort of perfume has [this or that] in it?”

John Biebel: I know people are very curious about how you got started into perfume.

Mandy Aftel: This is going back maybe thirty years, because I've been doing this for a long time now. I started out as a psychotherapist, and I'd written a book on plot and narrative called “The Story of Your Life” …after that I decided I wanted to write a novel and I was going to make my main character a perfumer. I really like research: My first book was about Brian Jones from The Rolling Stones, and I went into it and met all these people in rock and roll. So, for this novel, I wanted to do the research about natural essences (I knew that most of perfume was synthetic) and I like old books and searching for things, so I started to study about how perfume was a long time ago, and from there I took an aromatherapy class with a friend where I made a solid perfume. I had this strange familiarity with materials – I could find my way through the naturals; I loved them right away. It was research for the book, but I fell for those materials in a big way and it hasn't stopped. My friend and I said “Let's start a perfume line," and we did and it was called Grandiflorum Perfumes; I had that before Aftelier.

Mandy describes how she left that business and for a time stopped working directly with perfume, but the research continued. And with that, so increased her urge to write again.

MA: By then, because I am an obsessive kind of person, I had a hundred books at least [on perfume] and my best friend and editor (who I had written “The Story of Your Life” for) said “Why don’t you write a book about perfume?" And so I wrote “Essence and Alchemy.” It had this kind of terrific reception around the world and it got published all over, in multiple languages, and a lot of people started with that book.

But she didn’t know what to think about her business sense, and went back into it very slowly.

I thought I'd just make custom perfumes – like doing something once and not having to make it again. So somebody requested a perfume, so I made one… and then I made another. I had no business plan I had no idea what I was doing! None whatsoever! I’m also on the periphery of the food community here in California, and then after I did my “Essence and Alchemy” book tour, I was very interested in people who cared about ingredients (because I care about ingredients,) so I asked a friend if she knew a chef that might be interested in what I was doing, and she suggested Daniel Patterson. He's a person I've written two books with. He has three Michelin Stars, he's a terrific chef and we did the book “Aroma,” and then I very slowly added the Essences for Cooking [to my website.] Everything I'm doing now, except the museum, I've been doing for about 25 years. Custom perfumes, teaching… so I do about five different things, all of which I really love including my perfume line which is most important to me, and after that is my little museum which I opened up a year and a half ago.

JB: You do so many things… First off, I know that “Essence and Alchemy” had a tremendous reception. It seems that it was a gateway for a number of perfumers. Many read that book and it started them on a path.

MA: A lot have told me that, yes…

JB: From what I've read, the book opened up some consciousness for people about the connection between smell and the brain and cultural aspects [of perfume] and it's started a bigger conversation about all of those things. It’s significant in that people have riffed a bit about some of the ideas that you stated…

MA: Three countries are publishing the book this year [two of which are Brazil and Czech Republic.] It's published around the world – there are nine different language versions out there. One thing that was nice about the book, both people that work in natural perfume and people that work in mixed-media liked it, even though I only work in naturals. I'm not on a soapbox about naturals.

JB: I wanted to mention that, because there are some “soap boxers” out there, and then there are some cool and interesting folks who simply say “This is the palette I like to work with and I want to invest my time and explore this deeper,” as opposed to saying that I have this huge pallet that's going to take me forever to get through. I see you're almost giving yourself more time to do a deeper dive into the natural palette you've chosen, and you’re probably more intimate with the natural things than some people who mix all the materials up…

MA: I do love them, I love the shape and texture of working with them. They're my preferred place to go artistically and I care a lot more whether the person who’s making the perfume is an artist and is honest about what they do. That’s more important to me than anything else – being honest about what you do. I like artisanal perfume in general, I like very much when there’s a “maker” there, and a sensibility… and if they work in all-naturals (and that may be my way of working,) that’s fine. Some people may be on that soap box, but I’m not.

JB: I'm really curious about the whole flavor palette and all the work you've done with that. It opens up another conversation about the connection between smell and taste and how there's not much disconnection between the two. Can you tell me about that work of yours?

MA: The last book I wrote called “The Art of Flavor” with Daniel Patterson came about because we realized that he created food, and I created perfume and that we were doing the exact same things. So when I say hello to people in the museum and I’m talking with them, I always say it's not that different from cooking. The centerpiece for me are the materials themselves or ingredients. I like the little nuances of difference in flavor – even within similar plant species… I find it completely exciting! A lot of what I understood about fragrance is absolutely applicable to flavor. There's a great connection and so much of flavor is smell, a lot of the materials for flavor are the same materials for fragrance, those industries are very allied. You can get fresh ginger (it's very different from dried ginger essential oil) and it says different things. Some of how I teach and think are about the facets that are inside an aroma or a flavor. Different varieties have different facets. And what happens is that when different things are made into a fragrance or a flavor, those facets lock together, and in a perfume, everything locks together.

I believe with synthetics you can get more strands that can sit without those facets, with natural isolates you get those too, which have really expanded what I'm able to do with perfume. But using isolates (which can be done naturally or synthetically) – it's just a different texture, different shape. For example when you're cooking and you're using basil, if you use a spicy Thai basil or you use a very linalool-rich floral basil, that could really change the way your tomato sauce will go.

In the book, Daniel came up with these four incredibly and simple but amazing principles about how to create flavor which are exactly the same for perfume. It was very simple, but they came out of two years of us talking…

JB: That's so cool though, that they translated almost exactly to the way that you work with perfume!

MA: I can tell them to you – They’re so universal and organizing – You start with the idea of How to Add Ingredients Beyond Two. The first rule is that if you have two things that are very similar, you need a contrast. The next rule is the opposite – if these things are very far apart, you need a bridge. If something is heavy, you need something to lift it. If it’s very high and buoyant, you need to ground it. So all together, it’s a structure, and I teach this in my class. It’s a way to begin organizing the voluptuousness of all these materials, and a way to allow you to be very creative.

JB: And this is more or less a framework within a foundation… to find some wholeness in something so it won’t float off the foundation, or won’t be too heavy so it can’t lift…

MA: I think making perfume is about two things: one is a deep understanding about materials, and the other is structure. You have to have some structure when you're creating, particularly with naturals. I mean just tossing a bunch of gorgeous naturals into a bottle… you may hit something once or twice but you won't get that far.

JB: Are there any particular items that have really captured your imagination for a long stretch of time? Elements that you use in your palette that you never seem to get bored with?

MA: That’s an interesting question and my answer might be a disappointment, but here it is [we both laugh here]: I do that all the time, but once I get there, I change. I've had an ingredient called fire tree which I love and it's a really weird one. I started doing a perfume on a blog with Andy Tauer and I was practically shoving it in with a shoehorn and I really wanted to work with it, and would always come back to it (I was so in love with it. It had this very weird and interesting dry down, days and days of dry down, and it kept moving and I wanted that long dry down but I couldn't get anything to work with it.) It took me five years to find a home for that fire tree, so I had a lot of experience with how it wasn't going to work!

A long time later I made this perfume called Palimpsest, which is about scrolls that have been scraped off and used again, old writing. I've seen things like it: brick walls with advertising on them, where the paint faded away and they put other advertising on them, and I like that layered aspect to it… This is a lot like what was going on in the fire tree and I thought “This is where this belongs.” The essence captivated me and I finally found a home for it.

So I tend to be most interested in the latest thing I've got. It doesn't mean I don't use my old friends, but now, for example, I've got this pine tar that I’m really besotted with, and I have a natural ambrettolide, which kind of gives you a chance to do with musk that which other people get to do with synthetics: very clean, very light, from ambrette seed, and I know that I’m going to work with those two next. I tend to also look to see if I’m repeating myself. I look at my perfumes as chapters in a book… I don't want to go in a direction that's too close to something I did before. I'll just retire a perfume, even if it's successful. I just take it out. I like them to keep going, to sit together as a whole line, so sometimes I'll retire something that's really selling well because I don't feel that it fits anymore for me. I have a page on my website of “perfumes past” and I’ll make a bottle or two for someone who requests it, but for me I tend to look at my work as a whole.

JB: I wanted to ask you a question about audiences and what they expect of you. I'm almost a little disappointed sometimes in the perfume world when they are petrified of change. There is this reformulation panic that ensues and I've often been this lone voice saying “Well maybe it's better now!” or maybe they've made improvements. It might be the devil's advocate, but I wonder sometimes why we don’t look at these new things we are creating now, as opposed to some folks who will only trust “vintages”?

MA: I think this is such an exciting time in perfume. There are so many artisanal people out there, so many naturals, so much going on… and I feel a person like me, I really, really love being small and hands-on. There's been a lot of opportunity for me to get a whole lot bigger but I don't want to. It's a miracle that I'm out there and people know my work – it's amazing! But I see this excitement when I teach people: perfume as a way of thinking, as a way of doing, a way of interacting with the natural world.

JB: I'm going to jump to something that you said, and I’m grabbing this quote from “Essence and Alchemy” …”It's no accident that odors are called essences and spirits, they straddle the line between the physical and metaphysical world,” which really struck me.

MA: Wow, that was good! [we laugh]

JB: Yeah! Well I have to admit I was selfishly interested in this because I love this notion of things that straddle two worlds. And I said, “Oh that is something that speaks to me,” Tell me something about where your head is going with that. Is it that we’re entering the unseen world, or a spiritual world, or a bunch of things mixed together?

MA: I am going to answer it, but I am going to preface it… you know, so many people pontificate about so many things. I try really hard never to do that. I'm very careful to be pretty “workman-like” about what I do. After saying all that, yes, I feel that there is a real kind of magic in the essences themselves and in working with them that has been deeply transforming and restorative. They’ve just taken me internally to so many places, and I love that they have such a rich and tangled history with us, across the globe, across time, and that they answer so many human needs and always have. People instinctively want to use these materials, work with these materials. They take you somewhere in your head that is not linear, it's hard to describe it. I feel that they are a real gift. They are not totally of this world.

The perfume organ at the museum

The perfume organ at the museum

And so one drop of them can transform who you are, where you are, and they transform me and I see it weekly in the museum. I go there and I watch people – I have a huge [perfumer’s] organ and I watch what goes on with visitors, and their body language. I can see them connecting with something deep into the personal and spiritual. And I feel that's why people come back. You know that half my visitors are repeat visitors? And I think this is what drove perfume to be such an important art form. I think people really seek what this has to offer in their lives and it's not altogether of the material world because it disappears, it volatilizes, it's real but it's unreal, it straddles that line and continues to straddle it all the time, and I think that people understand that.

JB: I'm curious if your repeat visitors bring people back with them? Because I think that they would want to share what they've discovered. Is it like a gateway for them? and I imagine they probably want to bring someone with them through that experience again?

MA: Yes, yesterday someone came back and they brought their mother, and I got a mother who brought along her daughter. It’s become a community, which I love, and what happens is that people have memories specifically… But what's even more interesting is that some of them don't even experience a memory [in the museum] they just get transported – they just take off. There was a guy who came just last week and he was very happy – he's thrilled by something, he’s smelling, and he came over and said “I smell something and it don't remember what it is, but I'm having this experience. But I've never smelled it before!” He was just thrilled. I think language about smells is very far from smell itself, it can have too much control over the experience, so I'm always encouraging my students: Whatever language you have, that's the right one.

JB: And I appreciate what you just said about language because I've often told people (and I'm sure you've experienced this in your writing,) we've got so few words in English in particular to describe smell. It’s a really limited vocabulary. I find it in writing that my brain hurts as I try to find adjectives and nouns that will actually describe these things, so you do have to stretch and use metaphors… I find people will have these very automatic reactions to smell and sometimes use clumsy words because they don't have any language to use…

MA: Which is great! I think they're scared, but when I teach people in my classes, in my workbooks and a word “bank,” I’ve told them the best words, but also to search out their own words… What I’ve seen in teaching and workshops is that everyone's sense of smell is quite different. So I'll smell something and I'll say it smells spicy and they'll say it smells floral and I tell them whatever your words are those are the right words – don't let anyone say anything to you about that. I feel like it's such an animal part of us, and language is far away. You find your own lexicon, you find your own way through. Someone came in yesterday and said “I really love this stuff, but I don’t really think I have a good sense of smell.” I wrote about this in my book “Fragrant,” and I said to him, everywhere you go, start shopping with your nose. Everywhere you go, start ripping up leaves, start smelling the end of a piece of fruit, everything – start putting your own words to that, and it'll start getting better. You just need to bring your consciousness to it and it will improve.

Leonard Cohen

Leonard Cohen

JB: I’m going to shift gears – you’ve had a lot of quite high profile clients, I went down the rabbit hole of your work with musician Leonard Cohen. It must have been incredibly exciting to work with him.

MA: I made perfume for him for 20 years and it was a privilege and an honor.

Mandy then turns her computer to show me these beautiful drawings of Leonard’s lyrics, drawings that he made for her.

I had trouble charging him so we ended up in a gift relationship. [We laugh here] I would think: He's given us the songs, he's given these songs to the world, how could I charge him? Ancient Resins [body oil] and Oud Luban he wore all the time, and those are still in my line.

JB: I'm curious about your process in working with a high-profile client like him, or with someone you've just met – what does it take to make a custom product? What is it like for you, or have you gotten to a place where it's very comfortable to you to engage in a relationship like that with someone? What kind of questions do you ask?

MA: I'm not comfortable with it at all [we laugh] and I avoid it!

Mandy explains that sometimes receiving emails from Leonard could be slightly terrifying because of his artistic stature, but that working with him (and eventually his assistant) was a really rewarding process, one in which she got to understand his needs very well. However, making this a repeatable process when doing bespoke work is not easy, and usually involves the client becoming very engaged in the process themselves.

Mandy working on a custom perfume

Mandy working on a custom perfume

MA: I always start with a person's response to the essences, so I only do it in person. What I do is sit with a person and I show them different top, middle, and base notes, and have them smell and decide the ones they positively adore – really, really love… and I have them rank them. I also want them to know everything that's going into their perfume. I also do work for brands [here she mentions a major client for whom she is working, a business used by nearly all our readers.] But I always feel that people need to come to my studio and smell things. I've turned down many, many big clients because I don't think I can do as good a job because I need to have this personal interaction.

I remember a major experience for me, in my earlier career. A woman came for a custom perfume and she was incredibly corporate-looking, she was very conventional and I immediately judged her as being this very uptight corporate person. And when we sat down with the oils, she picked the wildest, craziest stuff that I had – funky, strange, sexy, and I said “You must have a very interesting inner life!”

And I thought, “No more!” as to assuming how people present themselves. So when I would get asked by a magazines things like “We have a sporty mother who drives a Volvo who likes to garden, what sort of perfume would you suggest for her for Valentine's Day?” I used to say “I don't want to be asked!” so I wouldn't do the interviews because I thought “I have no idea who this woman really is inside.”

JB: That leads me to the actual work that you do, and I don't want you to give away secrets, but I like the fact that you talk a lot about your perfume organ, it’s visible and open in the museum so it doesn't seem to be shrouded in secrecy. Some people are incredibly obfuscated about what they do, and you aren’t, which I think is really cool…

MA: I teach people exactly the way that I have learned how to do it – I'm very interested in being honest.

Civet and hyrax at the Aftel Archive of Curious Scents

Civet and hyrax at the Aftel Archive of Curious Scents

JB: Do you have some ideas that are halfway there, and some are things that you're always working on, for years, that you want to bring out? Or are you working on something that you just want to see come to a conclusion and send out there?

MA: I'm a very immediate person. It depends on the perfume, but they are their own thing. So for example my perfume Memento Mori, which was a very emotional perfume for me, it was about the loss of somebody that I loved, and… kind of the smell of their body… and I got some really terrible reviews about it in the beginning… and it's turned out to be incredibly popular. It's very surprising, and it was very risky, I knew it was kind of weird. I make some [perfumes] that are truly weird and I make some that are truly beautiful and that one, interestingly enough, followed the entire progression of the relationship: It was there, It wasn't there, It was good, It wasn't good… it's like the way the dynamic of the relationship was in the first year.

I try to capture a feeling. All of my perfumes have two elements: First, a conversation between two essences, which are the pillars of the perfume. They are the two things that are the most important aspects of it; and the second element is capturing a feeling. So Memento Mori just followed that process. It was very hard to make, but I tend to stay with it. Then some of them are easy to make and they just kind of drop out of my head, full force, there on the table. I like the ones that are hard. I also like the ones that are easy but I don't tend to go back. If I don't get it completed, I don't leave it, I just throw it away.

JB: There's something exciting about that – it's almost like the notion is not relying on these past ideas, but being willing to move on…

AF: I had this frankincense that I bought from this guy in Kenya, and he'd disappeared… and we got this better frankincense, and I didn't want to have to sell off the old one, even though it was perfectly “fine,” so we threw it out, and our trash smelled incredible [we laugh.] I don’t stockpile stuff. I’m not sentimental, and I’m not sentimental about the past. I like the whole hunt, I like the time-consuming aspect [of the research] I like everything that lets me stay small – truly stay small.

JB: I find that I’m starting to get a certain sense of things where sentimentality is nice and all, but it’s a trap. It can become a trap. Before I used to have a reverence for it.

MF: I love what I’m doing everyday. I get up and I'm grateful and excited… I'm familiar with my past, but I kind of like “now.” I'm better at doing things, I like that. I don't want to revisit all that. Sometimes I look at my old perfumes and I think I'm better than that now. Should I retire this? Is this still really valid? I like the idea that life is in front of you and that you're still growing as an artist: I really like that.

JB: To go back to that idea about your perfumes being conversations between two elements, your Cuir de Gardenia extrait, immediately I thought about the conversation between gardenia and leather. Is that the beginning of a conversation between the floral and the animal?

MA: It's interesting, I got both of those ingredients through students of mine – I used to sell the gardenia (I'm still selling it on the website,) but I only have 12 bottles and then it's over. There's a man who had made tiare absolute and I was able to get it, and I may be the only person on earth who had this particular stuff, and I always knew he'd stop and it would come to an end. When I first got it, I was blown away. A student of mine traveled there and met him, and that's how I got that. The castoreum I got through a student of mine who lives in a remote part of Canada.

One of the ideas [with Cuir Gardenia] is a sexy, dirty, “bad girl” perfume that I just feel those ingredients were made for, I just love the connection between those two materials, it was magic. The trick with that perfume was to not mess it up. Sometimes I start to build a perfume and I try to add more facets but I have to make sure I don't mess up what I began with.

Solid perfumes in antique cases

Solid perfumes in antique cases

JB: This is a question I wanted to ask you and it's even personal for my own work: One thing that I've had to learn is what things to take out, because I start to overwork something. That's something that’s frustrated me because I’ve worried “It's not as complex!” But now, I don’t want to dilute the initial work I’ve made…

MA: When I teach, I say, “Just because you like it is no reason to put it in.” It doesn't really matter if you like it, it matters if the formula is calling for it. Make a different perfume if you want to. Putting it in makes a difference, there's a wholeness to perfume as an art form and that you need to go back over everything you've done and make sure everything is needed. When I'm teaching or looking at my own work I'm always saying “What is this doing, who is this communicating with,” because I think of the oils as people. Who is this communicating with or could someone do the job better? I’m sure you do this with writing, do you need all these words? Could you take some of those words out? And with the perfumes: making sure I’ve got the right one there, and that they’re doing a job. Everything in a perfume is doing a job, and if they’re not doing a job (past your initial few choices), then it’s not a well crafted perfume.

JB: I wanted to talk about your perfume Cepes and Tuberose – another wonderful conversation-perfume…

MA: I made this perfume for my book “Aroma.” Daniel and I picked out these twenty five elements, and I had to make a perfume or a body care item for each one and we got to cepes, and I smelled this tuberose, and I noticed that it had this very earthy facet at the base and that was unexpected. I knew that they would lock together. When I did make it, I read reviews (when it came out about 20 years ago,) and there were these horrible reviews about it! People were saying “Oh, what is she thinking, how could she? This idea of using these wild mushrooms?!” But I remember I was so grateful for Robin at Now Smell This for putting it in a list of 100 perfumes that every perfumista should try and it ended up being incredibly successful. Putting porcini mushrooms into a perfume twenty-something years ago was completely weird!

JB: I don't think that note came back again for about another ten years… I didn’t see a mushroom note for quite awhile again, so I think that was very groundbreaking.

Are there some thoughts you have about people who are making perfume, or about the current landscape of perfume?

MA: My very first thought is to be honest, because the honest stuff is really terrific. Use less “stuff” in your perfume. Get control over what you have and ask yourself “Why are you adding this, is it really carrying its weight in a blend?” Skip the market-speak, which goes back to being honest, not so much puffing up. Work on your craft, continue to work on what you're doing and put out a perfume when you feel it's really fantastic. Take your time – work on it, throw things out… One of the things I say is “The world doesn't need another bad perfume, there are enough of them out there.” [We laugh.] I think it's important to express who you are in your work which means you won't please everybody which is fine.

JB: That's really important to know, and I wonder if that's a hang up for some people who are making perfume, because they’re petrified of making something that won't please everyone. That can almost become a paralysis.

MA: I think the customer is very savvy and very hungry for something that's authentic. So what I think what actually works is making something that is very real and very beautiful to you, and finding the right customer for that. People are deeply interested in stuff that's quirky and different and not like what you did before, even if it takes some time… and I saw that with Memento Mori, where it wasn't like a conventional “beautiful" thing I had made before. There's also no overestimating how important it is for you to be truly interested in what you're doing.

JB: I wonder if part of the great trajectory of perfumery (whether it's a hobby or a career) is the fact that there's virtually no end to study? I've never seen a part yet where one reaches an end. It seems like you could study these materials forever…

MA: But I love that! I have 145 turn-of-the-century books and you can see the fascination they had with learning, going all the way back to the 1800s when they thought these materials were for medicine. It's endless, it’s exciting, it's so wonderful – I mean, I show no sign of knowing a lot or reaching the bottom of it yet. I remember there's a quite well-known perfumer I know who works for a large house, who always says to me “Well Mandy, are you still only working with naturals?” And I'd say “Yes!” and he would say to me, “Aren't you bored?” And I used to think, and I’d say, how could I ever be bored? Every time you put something together it's something else, it's new, it's completely new: You put rose with clove it's one thing, combine rose with ambergris it's another thing, and as you bring in other things it's completely different. It's like saying are you tired of words so you don't write more books! [laughter]

JB: One material I’m most confused by is vetiver – and when I started, I bought a small amount and it smelled really grassy, and then I bought some more and it smelled like bacon, and I thought, “What the hell? Every time I buy this stuff it’s going to smell different?” But then it showed me a valuable lesson, that each of these will always smell so different. And I remember being upset because I thought, “What if I get a batch of something and I can’t get it again?” but then I thought that I’ve got to embrace this, that’s the truth of these materials.

MA: When I do find a vetiver, for example, I will sample ten of them and pick the one I like the best. I do it with isolates too. All the natural isolates, they're also vastly different from each other because they're contaminated when they're extracted from an essential oil. So if I had a vetiver which is grassier I know I also have one which is which is woodier – I may need to add something whose facets will push it that way. I had this rose I liked (in the beginning of my career) from Morocco, which was light and incredibly gorgeous, beautiful and got along with everything. Then I got connected to a grower in Turkey and his rose was completely voluptuous, it was really big, and really full of facets and I dropped my Moroccan rose like a hot potato. I stopped putting it in everything and I moved over to the Turkish one and I had to reformulate everything. I see that as part of the work I do.

JB: Yeah that's where I think your technical skill comes into play, that's where you must be able to smell when something is different, or recognize when you have to neutralize something… or notice that there’s an extra thing here, or something is missing…

MA: That's why artisanal perfumery is popping and happening and exciting and interesting!

JB: So I'm compelled to ask what's next? What have you got on the burner now that we’re well into this year?

MA: I have a perfume I'm working on now which is one of the ones that drives me wild. I made it, I made it all the way and signed off on it and… then changed my mind. I wake up in the morning, and I change my mind and I think “Maybe not…" so it has to hold for a while. So I'm there with this perfume right now but I also want to do a book about the museum. The museum has been the most amazing and satisfying thing that I've ever done in my life. I really love it and I was thinking I wanted to do a book which is an experience for people who either can't come to the museum or have come to the museum. But I don't want it to repeat the experience. However, I do want you to have a transformation from reading it. So I don't want to have photographs, I want to see if I can manage to do some scratch and sniff elements so that people can smell things as they go along. I don't want to provide (like my other books) super historical information; I want to riff on things, be more poetic, a bit philosophic. I also have all of these old books on plant materials and I want some of that to go right into the book. The people who were discovering this material about essences a hundred plus years ago, their language was so exciting and so fresh, so particular, so gorgeous – I want to share that writing about the natural world in this new book so people can experience all that turned me on, because this is what excited me when I shared this in my books.

Somebody came in yesterday and said “This is so exciting, this is so thrilling!" and I said to him "I feel the same way!" I feel like it all visited me, if that doesn't sound like I'm nuts… I feel like things visit me. Leonard Cohen once said in an interview that someone had asked him “Where do the songs come from?" and he said he doesn't know: If he did know he'd go there more often. I kind of don't know, even though it's me that did all this. I don't know how all that wonderful stuff landed on me, mostly with "Essence and Alchemy,” but I'm deeply grateful for it.

|

John Biebel is an editor for Fragrantica living and working in Rhode Island, USA. He began writing for the site in 2011. He holds a degree in Fine Art from The Cooper Union in New York City and works as a software application designer and a painter. He began his own indie perfume venture, January Scent Project, in 2015. He has a particular love for perfume history, the chemical composition of perfumes, and interviewing perfumers when he travels. |